Or “The Ungrateful Bias of Reductive Materialist Ontology in Archaeology“

This week I attended the ASSC 2025 conference in Heraklion, Greece which opened up an exciting opportunity to visit the Palace of Knossos and the National Archeological Museum. As much as Knossos is fascinating and appears to be an eternal riddle together with its symbolism, I found myself to be disappointed by the narrow explanations of ancient mysteries, symbols and rites that usually begin with a descriptive and dry materialistic interpretation of a certain object or symbol and end with a declaration that “the purpose is not clear”. I wonder, has anyone considered that ancient civilizations could have actually had a science of consciousness—a non-materialist, nature- and harmony-oriented pragmatic relationship with emotional wellbeing, overcoming our suppressed potential for transcendence and epiphany?

As a bit of background, the study of ancient human cultures has long been shaped by the foundational assumption that the hallmarks of “civilization” are primarily material: urban settlements, monumental architecture, metallurgy, agricultural intensification, and written language. This framework, which emerged in 19th-century European scholarship, continues to define archaeological inquiry and the public imagination alike. A dry, reductive materialist orientation carries an epistemological limitation and a streetlight effect, or the tendency to search for evidence only there where the “light of attention” allows one to look. In doing so, and without partnering up with complementary non-materialist viewpoints, it privileges the durable traces of human activity as we understand it today, while systematically occluding the possibility that ancient societies may have developed forms of knowledge and practice whose sophistication was manifest primarily in domains of ritual, rhythmic nervous system entrainment, theophany and psychospiritual cultivation. (Graham Hancock vs Flint Dibble debate at Joe Rogan is a good example where one can see the way in which opposing ontologies shape interpretations.)

From the earliest systematized excavations in the Near East and Mediterranean, scholars established methods and criteria by which the emergence of civilization could be measured according to the their epistemologies and ontological frameworks. This is inherently so, but complementary views shouldn’t be dismissed—if there’s any pragmatic truth to constructivism, which seems to be the case, we shouldn’t underestimate the power of belief in the way in which interaction and communication with environment and nature is taking place. Beliefs shape worlds.

For instance, the development of metallurgy and writing systems were taken as definitive thresholds distinguishing “prehistory” from “history.” This reductionistic framework, though important for standardizing archaeological practice, nonetheless carries a profound bias in that it reduces the very notion of civilizational progress to material accumulation and technological intensification. Stone, pottery, and metal survive millennia; sonic and psychoacoustic phenomena, pragmatic understanding of sympathetic resonance or entheogenic rituals rarely leave unambiguous residues. They need to be re-experienced to be understood. The result is a selective visibility of certain kinds of past human activity, which in turn entrenches the conviction that what can be most easily documented must have been primary to cultural life. As a consequence, other possible modalities of cultural sophistication, such as practices of collective ritual (e.g., Orphic rites in Knossos) and psychospiritual technologies of meaning-making are viewed as epiphenomenal or superstitious rather than constitutive.

I think we’re making a big mistake.

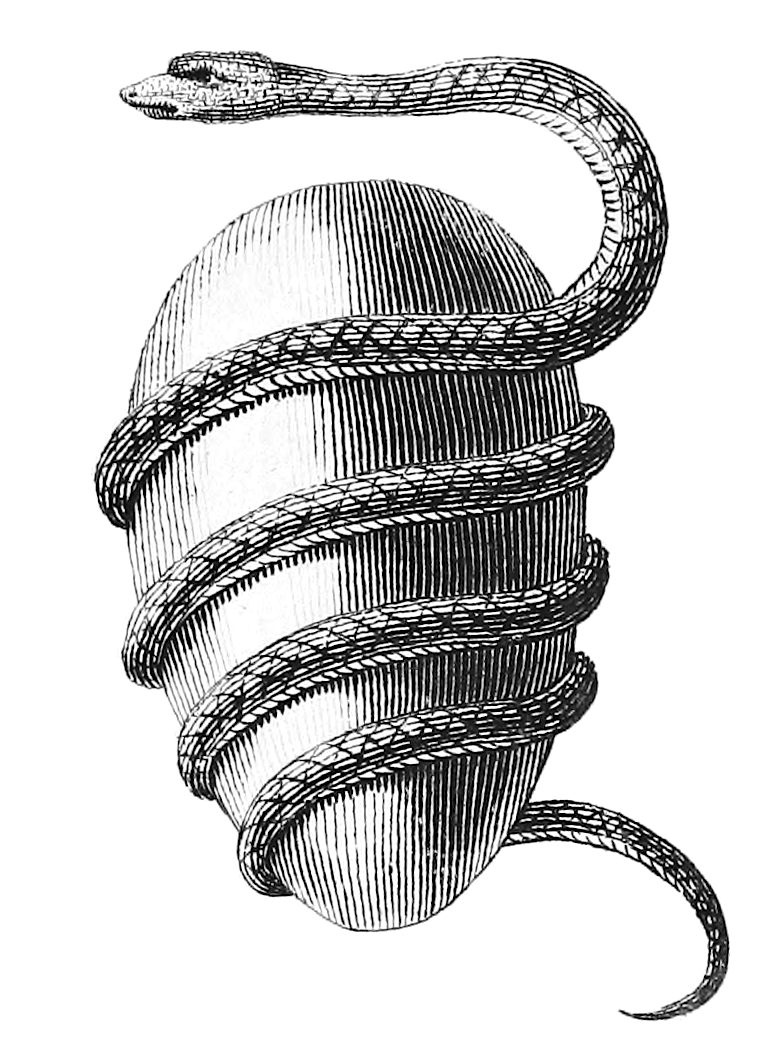

The Eleusinian Mysteries in ancient Greece, which employed psychoactive kykeon brews to induce experiences of death and rebirth, exemplify this orientation. Similarly, Orphic rites, Vedic Soma ceremonies, and shamanic drumming traditions demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of techniques for modulating attention, emotion, and the sense of self through rhythmic entrainment and entheogens. These practices are not reducible to superstition or primitive religion; they could be construed as psychotechnologies, methodologically developed protocols whose traces and remains we still struggle to decode. Such protocols and “mystery rites” seem to have functioned as the central organizing principles of entire cultures, guiding ethics, cosmology, and collective identity. Instead of writing computer codes that will crack the principles of consciousness, I suggest we start focusing on subjective experience.

The epistemological challenge in reductive materialist archaeology becomes apparent when we examine the interpretive reflexes that arise in response to anomalous or ambiguous findings. Sites with unusual acoustic properties, such as Barabar caves, are habitually interpreted as possessing only symbolic or ceremonial significance, rather than being recognized as potentially integral to systematic psychospiritual practices. Polished granite chambers are suggesting deliberate coupling of geometry and resonance that aren’t of interest to someone who hasn’t considered or experienced non-pharmacologically induced altered states of consciousness.

To conclude, I believe that an alternative conceptualization of cultural sophistication must entertain the possibility that ancient societies could have oriented their collective attention toward the systematic exploration of altered states of consciousness and could have understood many important things that allude our traditionally left-brain, individualistic and possession-oriented mindsets. The implications of this critique are not merely theoretical. They challenge the methodological orthodoxy by suggesting that the prevailing criteria for recognizing civilization are themselves culturally contingent projections, reflecting the industrial and materialist priorities of the modern West rather than universal measures of human flourishing or knowledge. If we accept that civilizations could emerge whose primary achievements lay in domains of consciousness rather than material production, then the absence of durable artifacts cannot be taken as dispositive evidence of cultural primitivism. It’s time to get in a circle and start figuring out what the Orphic bowl is trying to tell us.

What do you think? How to overcome this obstacle?

Thank you for reading!

Beata

For citations, use: Grobenski, B. (2025). Rethinking the Epistemology of Archaeology. Thoughts on Evolutions.

Leave a comment