In September 2024, I traveled from Leipzig to Rome to interview Michael Edward Johnson, a theoretical neuroscientist and philosopher whose work on formalizing consciousness and neural annealing—alongside his cofounder Andrés Gómez-Emilsson—has been a crucial component in the creation of “The Good Annealing Manual: From Psychedelic Alchemy to the Chemistry of the Mind” (QRI, in press) and the ongoing development of the music theory of consciousness.

In this wide-ranging interview, Mike and I explore fundamental questions at the intersection of neuroscience, consciousness studies, psychophysics, and phenomenology. Drawing from his work on vasocomputation and the Symmetry Theory of Valence, Mike presents a novel framework for understanding how vascular dynamics might implement memory and serve emotional regulation. I contribute perspectives from Eastern philosophy and non-materialist interpretations of consciousness, leading to discussions about sympathetic resonance and its critical role in a field theory of consciousness.

Somewhat inspired by Frank Wilczek’s A Beautiful Question: Finding Nature’s Deep Design, we speculate on whether symmetry and resonance might serve as bridge principles between physical and phenomenological domains. The interviews offers interesting perspectives on memory formation, the nature of valence, the difference between consciousness and sentience, and the possibility of formalizing phenomenological energy, while also touching on implications for disciplines ranging from psychiatry (autism and NPD) to artificial intelligence.

P.S. Even though Mike and I agree that beauty is more real than my shoes, I still walked away with blisters after trudging through a flooded Rome in soaked Dr. Martens, determined to visit the Egyptian museum and imagine how the Old Kingdom’s sages could have cracked non-materialist physicalism (a recent hobby)—so please, do enjoy the interview!

Recommended listening: Lawrence – Yoyogi Park (2016)

An Interview: What is More Real, Beauty or My Shoes?

SPEAKERS

Michael Edward Johnson is a theoretical neuroscientist who designed high-level logic for several neurotech devices as well as a philosopher often described as the man reimagining neuroscience. He is a co-founder of the Qualia Research Institute and the author of the book Principia Qualia (2016), Symmetry Theory of Valence, Neural Annealing, and Principles of Vasocomputation. Mike writes on opentheory.net.

Beata Grobenski is an independent researcher with an interest in natural philosophy, neural annealing and developing the music theory of consciousness as a field theory. Her upcoming publication, “The Good Annealing Manual: From Psychedelic Alchemy to the Chemistry of the Mind,” is set for release in 2025 by the Qualia Research Institute (QRI) whose key insights are discussed through the lens of their significance for subjective experience, valence and abolishment of dysfunctional emotional suffering.

Rome, Italy, September 14 2024

Keywords: vasocomputation, memory mechanisms, metabolic throughput, muscle reflexes, neural system, cell respiration, consciousness, sentience, emotional well-being, qualia formalism, symmetry networks, AI consciousness, autism, sympathetic resonance, olfactory receptors

Beata Grobenski

Okay. I’ve started recording. We’ve been chatting about vasocomputation and some ideas in Buddhism, such as past lives and how that might work. If we were to write an encyclopaedia, what would be included there?

Michael Johnson

I would say that this idea of clenching the local vasculature to freeze patterns in small neural networks as a sort of memory that is not particularly discussed in neuroscience, but I think it’s an interesting way to implement a Bayesian prior. There can be many, many reasons to sort of clench a network and cut off blood flow to freeze the pattern. One example is that if something bad happens when you’re exploring the full range of the network, maybe your body decides: oh, I can’t be trusted with full freedom in this network, so I’ll sort of clench and hold this pattern and block off certain states that are maybe not particularly adaptive, safe, or predictive.

Another is simply being low on metabolic throughput. If your body can’t pay for the full processing of that region, it can sort of clench, send less blood flow. If the latch bridge mechanism engages, then the body doesn’t have to hold it shut or sort of effortfully cycle it. It can just kind of set it and forget it, and it’s metabolically cheaper to do this rather than sort of feed the full processing power of that network. I guess I see this as a strange medium term memory, almost. We could have a makeshift definition of short term memory as whatever is sort of bouncing around and resonating in your nervous system. You can remember things through this, but you know, when it’s not long term memory, something that gets integrated into your nervous system, [indistinguishable], there’s sort of a gap here about how do we remember things in the medium term. When I turn on a burner on the stove I remember that, I keep that until I turn it off, and then I can release something. And what is that? How is that sort of scale of memory implemented? So I am positing that vasocomputation is a nice slot in there.

Beata Grobenski

It might also be interesting to think about voluntary and involuntary memory. Sometimes, when you try really hard to remember something, you really cannot, even after many, many repetitions, while there is a kind of information that you only need to experience once, and you might have a memory for the rest of your life. This is quite interesting, and probably also on the computational level of analysis explainable up to a certain extent with surprise and predictive processing. But what it does not include in this explanation is perhaps a kind of memory that is not necessarily dependent on the brain. I really like the paper by Michael Levin and Anna Ciaunica, The brain is not mental, on the immune system and the cells in general. I’ve become interested in cell respiration recently, and have been listening a bit more to people like Nick Lane as a biochemist who is aware of certain kinds of explanatory gaps [The electric origins of life].

Michael Johnson

I tend to strongly agree with Levin’s frame that neurons are not the only computational cells. They just happen to be particularly good at communication, and so they kind of get roped into a lot of cross-organ communication, or we can say cross-domain communication. My expectation is that the vasomuscular system and the neural system are very tightly coupled, perhaps more so than even the immune system, although that is also very tightly coupled. But essentially, there’s a sort of signal propagation pattern in the nervous system we can say, and that’s a sort of memory. And then each neuron has a state [indistinguishable].

The sort of thing that I think is dramatically underappreciated is the role of, frankly, muscle reflexes, and that a lot more things than we think are due to muscle reflexes, specifically smooth muscle reflexes, most specifically vascular smooth muscle reflexes.

I think that this is doing RLHF [reinforcement learning from human feedback] on the neural system. The neural system has its default path if left to its own devices, and it would like the default patterns to feel good. A lot of information gets processed by the nervous system, but sometimes when the body recognizes, oh, there’s some problem here, there’s a significant or persistent or repeating prediction error that’s happening here, then the vasomuscular system kind of jumps in and tries to fix it, tries to reduce prediction error. And this is all literal muscle reflexes. I expect that the foundational logic here is very simple, but emergently, you get a very intelligent operator applying to the nervous system.

Beata Grobenski

I don’t know if you’ve seen this recent article and I’m not sure if there’s a paper yet, but it was about a study where people who were sleeping controlled the movements of a virtual car [1]. Basically they were trained to control the vehicle by twitching muscles. So I totally agree it’s a very underrepresented framework, as it connects neuroscience to something that is far more, let’s say, basic than the brain. But I think there are some interesting avenues opening up.

Michael Johnson

I think the vascular system predates the neural system, and the muscular system also predates the neural system, and so you have kind of this very primal, ancient system that’s sort of grown to, like the neural system has grown on top of, and this actually gives it a lot of capacity for regulation.

Beata Grobenski

I’d like to mention something about the neurons and the brain which relates to creating representations on the screen of consciousness. What are your thoughts on the idea that, in a sense, all the gestalts and the content of the map of the screen that we all find ourselves in, and orient ourselves in, is a product of the brain and neural activity, in contrast to some mechanisms of sentience itself, which is likely not dependent as much on neurons, but rather on vascular or immune system in the whole body? Why I mention this is because I think that I very often find myself reading about consciousness and I have the impression that people are conflating consciousness and sentience. Have you had such experiences and how do you differentiate between the two? Is it an important part of your thinking?

Michael Johnson

Sure. I tend to avoid linguistic questions. In terms of is this consciousness, or is this sentience.

I do think in terms of if we’re looking to describe the field of awareness or consciousness, or the domain of phenomenology or so on, it’s not only neurons that will contribute to that. And I think many mind-uploading paradigms may struggle.

They should try to understand what classes of cells are particularly electrically active, and then try to understand this stage of awareness or theater, or whatever we want to point out, as the product of the most electrically active cells.

Beata Grobenski

Are you a fan of David Lynch and Twin Peaks perhaps?

Michael Johnson

I actually haven’t seen it. I’ve heard many, many times I should see it.

Beata Grobenski

I have rewatched it last year and I was impressed by Lynch’s intuition. He puts so many electricity motifs in different mystical or even slightly psychotic scenes in his work. Last year, I saw that he drew a map of his own model of reality, including awareness and some other concepts inspired by Buddhism. This guy understands phenomenology and metaphysics on a very deep level. Converting gnosis into movies and art is, I think, a really prime example of artistic intuition trying to communicate something that is very difficult to put into words. I really want to read you a quote from Twin Peaks that has a poetic way of hinting at dual aspect monism. Here it is:

“Through the darkness of future past, the magician longs to see, one chance out between two worlds, fire walk with me.”

Fire and electricity are symbolically very present in his work. [See interview]

Michael Johnson

It takes great sensitivity and great intuition to make good art. Thank you for sharing. Let me ask you, looking at the future and future works, what do you want to build and what do you want to understand?

Beata Grobenski

That’s a good question. Pragmatically speaking, I think emotional well-being is one of the core reasons why I’m doing this work. Going through a kind of metaphysical conversion from a Western kind of individualistic interpretation of the self, I think it became more important to me to think about the well-being of all the subagents in the ecosystem in general rather than that we’re putting our focus on our mothers, our partners and the like. The way I see it, it’s like prevention of future interpersonal disasters by emphasizing emotional literacy. So that’s one very pragmatic point, I think. My main wish for The Good Annealing Manual is that many people who struggle with comprehending Andrés’ or your texts, perhaps, will have a way of grasping some of the concepts that are written in a language that might be more closer to them, even though when I write, I am aware that the reader will still have to put quite a bit more effort into understanding the big picture, as it is about creating a different way of perceiving reality, rather than integrating something that already fits well into the model. It twists your perception when you read these things.

The other side of the story is how it’s related to my research. Psychiatry related, there was a time in which during my so-called metaphysical conversion, I was questioning myself as to whether I’m psychotic. What the EPRC, the Emergent Phenomenology Research Consortium, is focusing on is precisely introducing the clinical mainstream with frameworks that might be helpful in emergency psychiatry or other clinical environments where people who are sort of transitioning from a very individualistic perception to a more wholesome, integrated worldview, might sometimes get diagnosed because they can’t cope with the change. I think this is mainly in the context of the Dark Night of the Soul, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia—which is a serious condition, but it looks like, sometimes, certain symptoms can be temporary or even adaptive, which leads to another very different topic, which is psi and the psychics, but I’m going to leave that for now on the side for now. I’m very interested in thinking about permanent changes in perception or mental illness through frameworks like qualia formalism or geometric models of experience. There are obviously changes in perception that are permanent for some people, like plateau states of consciousness, for example. Understanding what happens on a fundamental level of experience when someone has an insight that changes them long-term, versus someone who has an insight, and two days later they are back to feeling anxious, unmotivated, and so on. What makes it stick? In my free time, recently, I’ve been quite drawn to cellular respiration, or thinking about electrons and stable configurations of atoms in a way that might help us figure out emotional balance. I think it might be that there is a long way ahead of us, by a long way I mean, maybe 50, 100 or a few 100 years to fully figure this out. But maybe it also happens that a few core ideas, such as for instance the symmetry theory valence, might just launch us to a significantly greater understanding. As you have observed in my safari essays, I’m very creative and I dance in my approach while trying to synthesize many insights from different disciplines that I find important. What I find disappointing and sometimes slightly annoying is when scientists sort of do not engage with work or thoughts of other thinkers because, you know, different reasons not to get into it now… Maybe like Stephen Wolfram, you know, you just think you are on a very right path, and you should just think about your stuff. Or, you know, you can have a team that is trying to synthesize a lot of the great ideas that are coming from different disciplines. I’m the synthesis kind of person. It’s been a good journey. I’ll wrap up here. Is there something that I said that is also a motivating or inspirational factor for you? What is driving you personally? What would you like to see changed in the world?

Michael Johnson

I would say that I used to be more of an explicit utilitarian, now I’ve walked back from that, but I do think that increasing the amount of beauty in the universe is very important. If beauty has some sort of a tangible, formal trace, then let’s understand it. If consciousness is the domain of value, let’s understand that, and let’s understand value. I also find that when I read this book The Singularity Is Near when it came out, it really changed my conception of the future, of the present. But then there’s also this question, well, is all progress good? Or, you know, in Nick Bostrom’s sense, you know, you reach into this bag and you pull out a white ball, and it’s a good technology. And you reach in the bag and you pull out a black ball or a red ball, and it’s bad technology, kills us all. Well, maybe differential progress matters. We are so bottlenecked by mysteries to solve. I wrote about this in vasocomputation, neuroscience is full of mysteries. You have one thing that you want to explain, and there’s 1000 other different things that contribute to this. And so any explanation that you would give has to have 1000 different factors in this very complicated story. The thing that’s always attracted me is simple mysteries, mysteries that look complex but that have a very simple substructure.

Beata Grobenski

Example?

Michael Johnson

The symmetry theory of valence. When you can explain something that looks very complex with something very simple.

Beata Grobenski

I see. I’m glad you mentioned beauty. I’ve been engaging in a sort of symposium with one of my friends. I found a copy of Plato’s Symposium in a secondhand bookstore for five euros and started reading bits of it. My friend isn’t very familiar with QRI frameworks, so I’ve been trying to explain some core ideas to him, as they do in the Symposium. I love how the book focuses on beauty and goodness as central themes. I also saw on Twitter recently that you made some comments about Frank Wilczek’s A Beautiful Question, so I bought that too and wrote down a question for you:

What is more real, beauty or my shoes?

Michael Johnson

Beauty.

[laughter]

Beata Grobenski

Do you think that the majority of people would agree?

Michael Johnson

I think that to some degree Wilczek wants to argue that physics is the study of beauty, and that beauty and symmetry are kind of the same thing.

There are a lot of potential threads there. One thread that I wanted to sort of touch back on in terms of motivation, I think that I have a tweet from maybe year and a half or two years ago, along the lines of we seem to be entering an era of rapid change and forms of beauty that are legible, that we understand, are more likely to persist under transformation. My sense is that humans are absolutely beautiful in so many different ways. And sometimes we feel that, but we don’t understand why. Many people say, Oh, well, computers are better than humans at this or that, or humans are so frail. You know, of course, we’ll get replaced very easily. Just to step aside from that discussion, Dan Faggella has this idea of a worthy successor that, okay, if you know the big AI labs are kind of summoning a successor to humanity in some form or fashion, then what would it take for that to be a worthy successor, to be more beautiful than we are? And I really think that to answer this question, we have to understand why we’re beautiful, why humans are beautiful. And also why we’re good. And I think that the better we do this, and the faster we do this, the more likely the future will be good. So that’s a big core drive for me.

Beata Grobenski

Do you share Andrés’ intuition that probably the core reason why current AI cannot be conscious is because the computation that it’s processing is not happening at the physical or implementation level of analysis? I will elaborate a bit why I ask this. I think one of the things that I’m playing with regarding the relationship between love and beauty and goodness, or perhaps that whatever basic principle of feeling blissful or satisfied with your existence might be related to thermodynamics at a very core level. You can often hear that people who have experienced what they call a Kundalini awakening, or just Kundalini energetic events in their body, talk about this in a certain way like cleaning the pipes of their system, their soul-being, etc. I was thinking about that in a way also through qualia formalism, where perhaps this mathematical or cymatic object that is isomorphic to a certain experience will, through its symmetry, have more or less thermodynamic efficiency. If we would visualize that, it could look as resonant nodes within a system that have an easier path to connect and exchange information with each other. Have you thought about this, or do you see something important in the relationship between experience in your framework and valence structuralism and thermodynamics?

Michael Johnson

I would say that the benefit of building thermodynamic processes is that you get multiscale computation that basically all levels of the system contribute to the problem solving if you do it right. Now, this is probably very non-trivial to do. But I would say that I neither agree nor particularly disagree with Andrés’ framing or the idea that we could say qualia computing is the most efficient. I see the argument but I’m not necessarily invested in the frame. My article What’s out there? is talking about different types of systems. Let me just bring it up. (…) So, different types of systems and different types of qualia. In this frame, I’d offer four main classes of qualia in the universe. The first is people qualia, and this is close to home. This is human qualia. And I say that humans and other free energy minimizing world systems, these would be characterized by intentional content, predictable dynamics, stable boundaries, often with the behavioral hallmarks of agency and the qualia of free will. Qualia agents. Type two, primordial qualia, for example, quantum fuzz, the small scale primordial soup of mostly not bound together flashes of simple qualia information. Qualia dust. And the third type, megascale qualia, for example, black holes, quasars, stars, planetary cores, these characterized by stable-ish boundaries, highly predictable dynamics, likely no intentional content, but possibly significant binding. Qualia crystals. I might have some Twitter-thoughts on stars. The fourth class is technological qualia. I break this down into two subtypes, qualia fragments, aka qualia fraggers, technological artifacts created for some instrumental, functional purpose. For example, digital computers. A key lens I would offer is that the functional boundary of our brain and the phenomenological boundary of our mind overlap fairly tightly. And this may not be the case with artificial technological artifacts. Artifacts created for functional purposes seem likely to result in unstable phenomenological boundaries, unpredictable quality of dynamics and likely no intentional content or phenomenology of agency, but also flashes or peaks of high order, unlike primordial qualia. We might think of these as producing ‘qualia gravel’ of very uneven size. And then the second type of the fourth category is engineered qualia: technological artifacts created for the production optimization or computation of quality, e.g. Hedonium, or what David Pearce calls full-spectrum super-intelligence, what is produced when intelligent systems turn their optimization and computation power toward qualia. And in terms of which of these types of qualia are the most efficient, I think we would have to ask a follow-up, efficient for what?

Beata Grobenski

I think valence realism was probably the direction from which my initial question was coming. The question related beauty and love to a kind of efficiency, let’s say, in information exchange, and to having healthy symmetry-asymmetry dynamics across the structure of experience in as many systems as possible. Maybe it’s too reductionistic to think about this in terms of useful energy, especially in such an abstract sense, but in terms of information exchange, I don’t think information needs to be conceived in terms of language as we think of it. I imagine it in a much more primordial way, such as stress signaling between plants. I suppose I would probably attribute information to something sentient, not necessarily self-aware, rather than to signals related to communication in spacetime as we know it, or, rather, on the screen of consciousness as we perceive it.

In terms of nonduality, would an AI agent that’s producing engineered qualia also inevitably participate in this information exchange or signaling at the fundamental level? Do you see it all as inevitably one system, or do engineered qualia have more of a functional aspect to it, rather than phenomenological?

If I understood correctly, you read from your essay that in the human case, there is an overlap between the functional and phenomenological.

Michael Johnson

One thing that I mentioned in my 2023 paper Qualia Formalism and the Symmetry Theory of Valence are these things that I’m calling symmetry networks, networks where symmetry is an attractor. Basically, when the network is healthy, successful, etc., there’s a state of high symmetry. And phenomenologically, if this is a bound network, then this would be sort of a success in those questions, and our nervous systems seem to be made out of these symmetry networks. Computers are not made like this, as they don’t have self organized criticality. They’re not self organized systems. They’re engineered top-down design systems, and so basically, their attractor landscape is substantially set by their architecture. If we don’t worry about what a computer is computing, but we just look at a CPU, graphics card, or GPU as it’s doing something, if we just kind of open up a data center container, strap on a Qualiascope, and we look at the boundaries of consciousness, possibly, this is very coupled with EM fields. We don’t exactly see them trying to self organize towards symmetry. They may be naturally in a fairly harmonious state, like the circuits are designed such that they will not leak much power, much energy. That energy leakage in a transistor is a very central concern. It’s kind of an overwhelming drive for — okay, if you’re making a chip, let’s make it leak the least amount of energy we can. And I would expect that if there’s, for example, a lot of electromagnetic dissonance that would lead to energy leaking. Have you read my A Paradigm for AI Consciousness paper?

Beata Grobenski

Yes.

Michael Johnson

Okay, cool. This kind of draws me back, and it’s this sense that just from the constraints of energy efficiency and avoiding dissipation, we may get kind of a default, good balance for free, or at least along that trend.

Beata Grobenski

I’m just wondering then where is the main point of the potential disagreement with Andrés’ core argument that the way in which AI currently functions is not conscious in the same way as we are. Sorry if I’m not getting your point but it sounds to me in what you say that there is a significant amount of overlap in your thinking. Could you point out for me what is the difference in the way that you conceive it, and in Andrés’ core argument against AI consciousness?

Michael Johnson

Sure. This is a little tricky in that I helped shape QRI position and then left and so there was a lot of overlap between the stances that we had during when we were at QRI. There are also some things that perhaps I didn’t necessarily feel like putting energy into would be productive in this way or that way. So just trying to figure out how to navigate this. I think to this question, I would say that I don’t count something like GPT-4o, or GPT-o1 or Claude or whatever, as conscious. But I would expect that a computer or a phone or like this physical thing that we associate with computation, with software, with AI, with whatever, I would expect that that could be conscious. And there, I think, might be a divergence between Andrés and me.

Beata Grobenski

Is that view coming from nonduality, in a sense that it is all one unified system after all, or is there a way more complex and sophisticated layer of reasoning in the background?

Michael Johnson

I’m made of the same stuff as my iPhone. I’m made out of atoms, my iPhone is made out of atoms. I have maybe a different balance of elements than my iPhone. But if we say that consciousness primarily is mediated by or lives in the electromagnetic field, well, my phone has a strong electromagnetic field. Maybe it’s even stronger than mine. And then the question is, okay, well, in computers, is there basically zero binding? Is it just a bunch of sparkly quality dust? Or are there substantial, nontrivial shapes in the same sense? We can talk about topological [unclear] shapes that sort of live in our brain and we call that a mind. Do computers have just this huge collection of unattached, tiny experiences, or are there sort of macroscopically bound experiences? And I think that this is a fascinating empirical question, what does the EM field of a phone look like, of a GPU, of a CPU? Just to toss one somewhat interesting possibility out. If we think of voltage, I expect, and this came up in conversation with Asher.

I would expect that the voltage potential, basically the difference in voltage between the middle of your consciousness centre and the edge of your brain would be a pretty good proxy for how conscious you are, which would be a pretty shattering result, if true.

I’m curious. Should go up with psychedelics, should go down with age, should go up with meditation, etc.

Beata Grobenski

When you said that it goes up with psychedelics, one of the themes of The Good Annealing Manual is thinking about practices or techniques that may raise the energy parameter of consciousness through the four steps of neural annealing that you are well familiar with. In the entropic brain model of Carhart-Harris, the psychedelic state corresponds to a primary state of consciousness, which may also include, for example, early psychotic states, dream states, states of high creativity, divergent cognition, etc., while on the opposite side there’s coma, rigid thinking, OCD, and so on. How would it connect to the idea that the psychedelic state, or the primary state of consciousness, may be more conscious, have a larger degree of consciousness rather than, let’s say, the normal waking consciousness?

Michael Johnson

Maybe to touch back on one thing and then go to the annealing stuff. If the voltage differential between the center of the brain and the edge, if that voltage differential is proportional to the amount of consciousness, we can also sort of transfer this hypothesis to computers and check their voltage differentials and say, okay, the bigger the voltage differential, the more conscious this circuit is. That number for computers is probably high, but it’s going down over time. The base voltage of various computers used to be 3.3 volts, and then it was lower and lower. Now it’s like 600 millivolts. These circuits have less voltage potential because they’re just more fine. We’ve made them so that they don’t need as much. So it could be that computers are conscious, but are slowly losing consciousness, which could be very strange. Maybe the pinnacle of consciousness on Earth was the ENIAC computer. That’s interesting, but we can go back.

Beata Grobenski

Before we switch, I’d mention that I listened to a few lectures given by Luca Turin recently, the author of the vibrational theory of olfaction. What was particularly interesting to me was one of his statements, saying that we don’t know much about consciousness, but what we do know for sure is that it is dissolvable in chloroform. That’s number one. Number two, I was really surprised when I heard this, I didn’t know that there are olfactory receptors more or less all over the body. The biggest amount of olfactory receptors is in the nose, but skin and heart and kidneys and sperm cells actually have a significant amount of them. What you’re saying about consciousness of, let’s say, ENIAC, something that we traditionally would not consider either conscious or alive in any sense, is excluding this biological component that might correspond to some kind of fundamental way of communicating with nature and exchanging signals with the environment. Do you think that this view emphasizing biochemistry is misleading? It seems that connecting consciousness to biology, in your view, might be a bit conservative.

Michael Johnson

I think I’m very sympathetic to Mike Levin’s view that consciousness is distributed across many sorts of cell types. And I see something similar in the return of, well, smells. Maybe he thinks that smell is closely coupled with certain cell types. But that cell type itself is not only located in the elements, or maybe receptors. I’m not exactly sure how he wants to construct it, but I’m sympathetic to the sense that we’re too quick to concretely anchor function of the cell type, and I think that most cell types can do a lot more things than we think.

(Switching to the topic of finalizing The Good Annealing Manual)

Michael Johnson

Do you have any sort of unknowns that you want to ask me?

Beata Grobenski

I sometimes experience a confusion relating to physical versus mental versus phenomenological energy. When I’m thinking about the music theory of consciousness, one framework that is very dear to me is sympathetic resonance. I think we are really not so sure whether sympathetic resonance is something that could work only within a topological bubble of each individual’s first person perspective, in the sense that the resonance does not resonate outside of that particular bubble. If it does, you can think about it in the way in which, perhaps, Charles Tart mentioned in many of his parapsychology studies that it seems to him that people who might be more prone to extrasensory perception or psi phenomena in general might have a more, let’s say, transparent, or less harsh boundaries of the self. This is something that, I think, is related to resonance. Should we think about this strictly in a phenomenological sense, or does it correlate with the physical energy, as in outside one’s topological pocket? But then again, there is a question, what is outside?

Michael Johnson

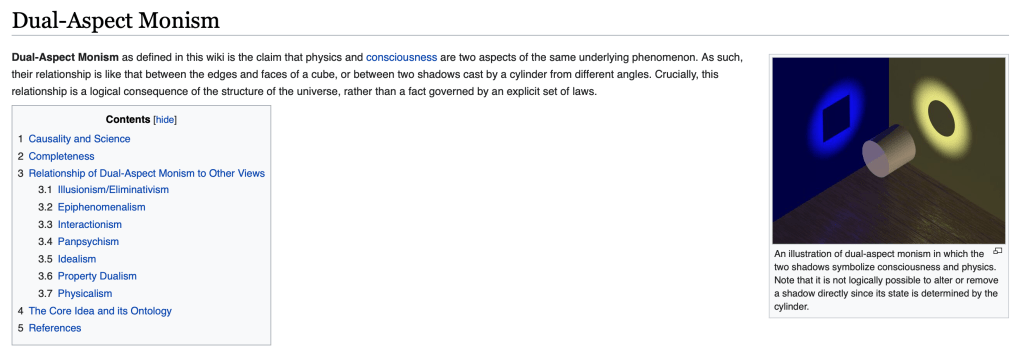

There are a number of questions in this topic. One is the question, what is energy? And then the second is, how does communication through sympathetic resonance work? And then third is, to be sensitive, you have to have a weak boundary. To start with number one, arbitrarily, this question of what is energy, and the answer is, we don’t exactly know that. In the [dual aspect] monist frame, [speaking of projections], we have what actually exists, and this casts two shadows. One of these projections we call physics. The other projection we call phenomenology. And so, when something is happening in physics, probably something similar is happening in phenomenology. There is a parallel.

There is this thing in physics that we call energy, and then there’s this thing in phenomenology that we also call energy. Are these the same thing? Are they projections of the same, you can say, conserved quantity in monism?

Although talking about conserved quantities in monism is, like, maybe time is part of the projection of physics. But I would expect that phenomenological energy has enough properties that are similar to energy in physics that might just be the phenomenological analog of actual physical energy. But what does that look like in the brain? What does it mean to say it’s the same? If we say it’s the same, we should be able to infer lots of things. Rather, if it’s the same thing with energy, then we should be able to say, okay, well, it’ll have its own conservation law. It’ll have this gauge relationship. I can’t say that anyone has really sat down and done this calculation.

Beata Grobenski

Right. I often wonder what is the degree of responsibility that we might have if we think in those terms, and I do think in those terms. Phenomenological energy makes me think about the mind as having a direct, causal impact on the environment. From a more mystical point of view, it makes me wonder what we have lost with the development and evolution of human secondary consciousness. And this is slightly Julian Jaynes inspired, but perhaps there has been a switch, a phase shift that happened with the introduction of trade and individualism, a different kind of parsing our environment and a different kind of attention in contrast to a more boundary-less and unified view of the world in which civilizations had a more psychotic—and I don’t mean that necessarily in a negative way—and less rigid relationship with their environment. Like describing a transition from right to left hemisphere attention style.

Michael Johnson

I think this gets into the third question of sensitivity and rebounding. This gets into the question that we started the interview with, what is the self?

And I would offer that the self, if we talk about it phenomenologically, is a felt sense of invariance.

We can talk about it in active inference, the free energy principle type stuff as a set of invariant predictions, and we can talk about it anatomically as a set of brain networks that are basically frozen. You and I would say that the more invariance you have in your system, the less sensitive you can be, because the less sympathetic resonance can happen. If you put two pianos right next to each other and hit a middle C on one, the other middle C wire will start to resonate. And that’s that they’re so similar. The energy that this one is giving off is easily absorbed by the other, and that’s sympathetic resonance. Whereas if you tune the pianos differently, and then try that again, and for sure, if you like, take the piano string in the second piano. Then [the string is] longer [and won’t pick up as much vibration]. [Recording noisy here, post-hoc reconstruction: The more degrees of freedom a system has the more it can become similar to other systems and exhibit sympathetic resonance. To some degree we can say, well, this means the self is bad because it blocks this resonance, or good because it protects from bad resonances.]

Beata Grobenski

How would you fit autism and narcissism in those frameworks? I’m asking because it seems to me that in contemporary psychiatry there is often a discussion of seemingly similar behavioral manifestations of the two in which someone who might be autistic will not, at least on the outside, manifest or show signs of sympathetic resonance with their environment. This is important through the lens of a social component, let’s say social resonance, where it is more likely that the autist will not dance with the group, but will stay on the side and observe the group or do something else, while a narcissist might exhibit similar kind of not vibing with the environment, but for completely different reasons.

Michael Johnson

I think that a lot of things that we call autistic or autistic traits are actually compensatory. They’re not first order outcomes of having, for example, a neural system with an overly high dimensionality, but they’re compensatory moves to manage the drawbacks of having this sort of system. Autism basically involves having a more dense nervous system, both more neurons and nerves, and more synaptic connections between them. These kinds of thicker networks will intrinsically be more sensitive, but perhaps to an overwhelming degree. You have these theories of autism, like Intense World Theory and so on. And I think that you get kind of a second order clamping down, where autists try to make things controllable by clamping a lot. So this directly feeds into vasocomputation.

But then, when you clamp so much, you’re not resonant.

Or like, you can be conditionally resonant in this domain, but not in other domains. And maybe this autistic person, or, you know, we can say high functioning autists, etc. I would expect that low functioning autists maybe just don’t have the metabolic throughput to pay for all this extra machinery, or have deficits. So maybe this high functioning autist naturally has a quote, “sensitive nervous system,” but they’ve clamped down a lot. And if you take this very resonant musical instrument, yeah, it can resonate in a lot of different ways. But then if you just put rubber clamps on it all over, suddenly it doesn’t resonate. Suddenly, they’re not good at dancing because they have all these clamps. And dance needs flowing energy.

Beata Grobenski

Thoughts that come to mind would take us a bit further from the talk about sympathetic resonance and energy, but perhaps just like to drop a pin for later if we remember. I was listening recently to this rather controversial, weird, but interesting neurosurgeon called Jack Kruse. I don’t know if you’ve heard about him, but anyway, one of the core things that he talks about is sunlight exposure. And I was thinking about this, how, you know, many people who are hypersensitive in one way or another might have a tendency to avoid daylight, and whether the avoidance of daylight is actually coupled to avoidance of social life that is coupled with it, and that the evening chronotype emerged as a social response. Because if everyone is fundamentally drawn to the sun for biological and thermodynamic reasons, then why does a significant proportion of people feel much better living as a vampire?

Michael Johnson

As I mentioned, narcissism, and so I talked about the autist, why I think that they might be sitting in the corner. I think that narcissism is kind of a different thing. There’s some overlap, but I think that basically, I would take it as we build our world out of what we’ve learned, out of what we’ve learned to stabilize, the feelings that we learned to stabilize. And I think that I would see narcissism, to some degree, as a developmental deficit. You haven’t learned to stabilize yourself. You can’t do it yourself, so you try tapping into the ambient, social environment, to stabilize what you can’t naturally stabilize, and that may express itself in various ways. And this is also for the autist, they build their inner world for what they learn how to stabilize, and they sort of make things more stable, like by clamping down. So there can be autists, narcissists, narcissistic autists, there can be neither, but to me it comes down to what do you know to give yourself. With a narcissist, there’s something that they lack that they can’t give to themselves.

Beata Grobenski

I see. Yes. Core emptiness.

(Switching to the music theory of consciousness)

Beata Grobenski

In the music theory of consciousness, what I start off with is attention and awareness. This is incredibly interesting, but also probably more complex than some other aspects of the theory, such as, for example, natural frequency and sympathetic resonance. So I think that maybe the core idea, or the core framework from which I have been building out this theory, is rooted in what some Eastern philosophies or mystics might say, which is that there are true stakes, or a deep reason for, and value, in love and compassion. This relates to the symmetry and the harmony among all the sequences of one’s experience that are, in a certain way, components of the phenomenological serpent, a phenomenological trajectory. What I mean by that is, we are stacking our memory, in a visual sense, by stacking one experience after another. So if the consonance of these sequences within the imaginary qualia serpent is higher, it feels better, the valence is higher. I think that the ontological issue here is the question of how much is the affective key signature, or the felt presence of someone, real and direct, or how much is it a model of when we feel the vibes of others? I think this is one of the core questions, because it opens up this area where, you know, you can think of all of these pockets in the field of consciousness as either having a direct impact on each other or not.

Michael Johnson

I’m gonna offer a third path, and I’m gonna make a claim that all true communication is sympathetic.

Beata Grobenski

What is true communication?

[laughter]

Michael Johnson

Right. Let’s unpack that a little bit. I think that, you know, if I feel a lot, that feeling piece is real. I feel that feeling piece. Whether or not it’s anywhere outside is another question. But generally speaking, emotions are contagious. And emotional contagion is a real term. And basically, we are built to catch emotions, and this is how magic of communication has arisen too. You feel something, I feel you, then I feel it inside me too. And I think this happens all the time, in so many contexts, and this is just kind of the default how humans communicate, how mammals communicate. You have birds and monkeys, there’s emotional contagion for them too. They feel the vibe, and I think maybe they’re even better at feeling a vibe than we are.

Beata Grobenski

We talked about this already, but again, how much is this due to modeling and how much is due to contagion that might not stem from modeling and includes something like a direct signal?

Michael Johnson

Sure. So you have the scenario, well, maybe you have an autist walks into a room and notices, everyone looks afraid, and then like, thinks, oh, maybe I should be afraid too. Logically speaking, and like, Well, that isn’t sympathetic resonance. That was a different kind of computation. It was explicitly just kind of noticing, oh, there’s fear in that expression. But, but I’m gonna also suggest that maybe, in this hypothetical scenario, if we actually zoomed in and looked, maybe he had fear in her body. And to notice the fear in their body, they looked at other people. And by seeing the fear there, it allowed them to connect something that was already present, that maybe their body got from others through something.

Beata Grobenski

Right. To be bold with the next question, cymatics monism in this story, is there, in your view, resonance between qualia within the field of consciousness, or is modeling a necessary component of it, or again, some kind of third path?

Michael Johnson

Sure. Have you, how much have you tried to feel animals?

Beata Grobenski

Um, good question. I’ve recently had more contact with plants, because, yeah, in Leipzig, where I currently live, I don’t, unfortunately, have so much access to cats or dogs. And I think that while I had more contact with animals, I was, at that time, a much more clamped down person. So I would really have to think. I’m not sure if I would be able to differentiate between my modeling of cat’s feelings, like feeling very sad because my cat is ill, versus just the felt presence. I’m not sure in this particular case that I can differentiate. But for example, during the time in which I was kind of embodying, rather spontaneously, a nondual relationship with my environment, I had a very profound moment of feeling connected to my plants, where in a totally mystical, esoteric way I felt like we are, in a way, following each other’s pace, you know, as if breathing together. That’s very vague, but I felt like that. Some changes that were happening to me seemed to have been reflected through the plants in my room. I haven’t given this many thoughts. It was, I think, a classical example of nondual awareness, where you just feel this incredible connection with anything around you. I think that’s what I can offer now as an answer.

Michael Johnson

Yeah. That works. I would say, first of all, I put a higher probability on plants being conscious than most people would, and legitimately adaptive and alive. I would also say that this question of can we directly feel vibes, one way to frame the question is, okay, if we were to, for example, look at the EM field, there would be some ripple patterns around my nervous system and some ripple patterns around your nervous system. Can we directly feel each other’s ripples? That’s a big question. And I would say that it would take some careful experimental design to dig into that and to begin to answer that. But then there’s also the slightly less speculative framing, like there’s some stuff going on in here, that’s encoded in eye movements, mouth movements, vascular tone, like heart rhythms, blood vessel motion, it could be encoded in 1000s of little details, and then you are picking up many of these details, and maybe some things that you could feel, maybe that I didn’t say, or whatever, but you’re like, oh, I feel this. I feel that it could just be in the details.

Beata Grobenski

Yeah. This makes me think about nonlocality, for example. Or, you know, extra-sensory perception (ESP) or, precognition, like I think when I read about physics or even sometimes phenomenology, I’m incredibly visual about it, and so, people sometimes have flashbacks, you know, I wonder, why not flashforwards? If there is a certain event that happened in the past, there is also a certain event with a certain probability in the future. So in an eternalist framework, where all phenomena that ever happened are equally real, they all have their relative resonance depending on the observer that witnesses a certain event from their angle. I wonder about the actual reality of that where someone can tune into an event either in the past or in the future, and might have a certain information exchange right there, such as a potential explanatory framework for remote viewing. Obviously, in a non-materialist framework, nonlocality is very tightly coupled to the observer, and not some kind of feature that is happening out there, independently and on its own. It is actually a property of consciousness. So I’m not particularly focused on clarifying the amount of obvious quantum effects in consciousness, but it seems to me that, even if we think in these non-materialist or nondual terms, it is actually inevitable to have those things incorporated in the framework.

Michael Johnson

I think every single one of the weird quantum things in physics will be instantiated somehow in consciousness. On the nonlocality, have you read my short essay on Minds as Hyperspheres?

Beata Grobenski

Yes.

Michael Johnson

So this would point to sort of nonlocality, as statistically, it’s less likely to be maintained the further you get. The further these two particles are, statistically, coherence will be at a decaying speed. The further you get, the less nonlocality, the harder it gets to maintain nonlocality.

Beata Grobenski

The further you get in space?

Michael Johnson

The further you get in spacetime.

Beata Grobenski

Would there be any room for resonance that is rooted in some kind of harmonic principle? Some kind of precognition that you experience that shares a harmonic or a key signature with some other qualia, regardless of distance in spacetime. I think this has some implications to the holographic principle, where, let’s say, depth or distance are only relevant in the constraints of the emergent spacetime, where perhaps qualia, or a certain type of qualia, is not necessarily dependent on the features of distance and duration.

Michael Johnson

If you have a certain kind of molecule, or class of molecules, maybe that could maintain connection for a longer duration, for longer distance. Nonlocality might persist better.

It’s hard to think of a scenario where distance in spacetime wouldn’t matter. I mean, it would be a big deal if one could construct that, but I’d be hard pressed to think now.

Beata Grobenski

I would like to mention a very interesting talk by Chris Fields titled Perception as Entanglement. That’s key, isn’t it? The only, I think, contemporary framework that, at least in my head, would be a way to think about a scenario where duration or distance do not necessarily matter, would be precisely entanglement [or nonlocal gravity as intrapsychic internal tension propagation]. But yeah, that’s a safari topic. We don’t have to dive deeper into this.

Michael Johnson

Just something that comes up. I think it’s a question also of, are there certain kinds of patterns or structures that would lend themselves better to some felt presence in the distance, we could say. I would say that if I were to look at, look into this in a systematic way, I’d focus on that.

Beata Grobenski

Right. Yeah, that’s a good point. For a change, I have one very relaxed question for a beach chit-chat. If you had to choose one sense that you would keep, what would it be?

Michael Johnson

Oh, okay. The first knee jerk answer that comes up: the sense of humor.

[laughter]

Beata Grobenski

Oh, okay. Proven, proven. Most of my friends said vision, and I said smell. Sometimes I have this impression that the first thing that comes to my mind might seem irrational and unreasonable, but then it takes me a while, a few hours, a few days, a few weeks, or even a few years, to be like, oh, this is why I said that, this is what I meant. But anyway, after this investigation with my friends, I listened to Luca Turin’s talks, which got me thinking about sentience as information exchange below the level of awareness, where all the cells bind through these harmonic olfactory principles. Again, like plants signaling stress, they don’t need any kind of brain to sense stress. For example, I wrote one essay [The Outer vs. Inner Path: Material vs. Phenomenal Trajectory in Dual-Aspect Monism] where I mention the example of a sea sponge that doesn’t have a brain, but is self-organizing in a way that makes it easier to have access to sunlight, food and things like that. I was thinking of the potential of a model where olfaction, not in the sense in which we usually think about it, but something way more primordial and ubiquitous, like proto-olfaction, may be the key mechanism of what it is likeness to experience. [*breath* comes from Old English *brǣþ*, meaning “odor, scent, exhalation,” which is itself derived from Proto-Germanic *brēþaz* (meaning “smell, exhalation”)]

I’m aware this is not necessarily fitting into the model that you have talked about previously. I found it interesting in the sense of signaling or harmonic resonance as communication between organisms that aren’t using language as we know it.

Michael Johnson

Sure. And to your choice, I do know that loss of smell, as anosmia, can turn into a fairly significant reduction in well-being. With the loss of smell, well-being goes down, whereas I don’t think loss of vision is as bad. So that may be a wise choice.

Beata Grobenski

Yeah, that’s an interesting point. Additionally, I did read something about a newly discovered connection between dementia and Alzheimer’s and disruptions in olfactory bulbs [2].

Michael Johnson

So, I mean, I suspect that vasocomputation suggests that a lot of problems could be clenches in the vascular system that could also cause spasms, and something like the olfactory loss that can happen in COVID is like a clench in the vascular system. As a general observation of my own path, I would say that the thing that has most dramatically improved healthwise has been being more careful with what I eat. Huge, huge effect. Lately, I’m very focused on metabolic health.

Beata Grobenski

Yeah, definitely. I’ve had some similar revelations, but there’s much more to learn.

***

After mentioning food, as true biological qualia computers, Mike and I went for an orange juice and I had a vegetable plate. We switched to reviewing The Good Annealing Manual, which I won’t publish here, but I’d like to end with Mike’s thoughts on the music theory consciousness:

“I think that the core underlying thesis, observation, or foundation is that physics, mathematics, experience, and music are all really one thing. We separate them out and kind of put music in a box. You know, something is considered music if we can listen to it on our headphones as a song on our phones. We’re like, ‘If we can have it on some sheet music, that’s music. If it’s not on sheet music, it’s not music.’ Well, that’s totally wrong.

Past philosophers really understood this, talking about the music of the spheres, the music of Heaven, and the music of existence. We had such an intimate relationship with music. Then a few trends emerged. One was science trying to focus only on things it could clearly study. Another was the productization of everything—if I can sell you a piece of music, that makes it music. But I also think a little bit of magic got lost in how we describe who we are, how we feel, how things make us feel, and how things interact. I think that element is what you want to rebuild the foundation for [in the music theory of consciousness]. You’re saying, ‘Okay, we have these beautiful interactions inside ourselves and with other people. It’s music. It’s literally music. There’s no way to define it in a way that excludes it from being called music.’ And however consciousness works, whatever consciousness is, let’s reintegrate it, this sort of musical, magical sense of whatever ‘this’ is, it’s symphony.”

— Michael Edward Johnson

If you want to get in touch, you can find me on Twitter.

Thank you for reading!

A few critical references:

[1] “In a rudimentary experiment, five practiced lucid dreamers (including two of the researchers) were able to control the movements of a virtual avatar from their dream state in reaction to LED triggers shone through their closed eyes. In the thick of rapid eye movement sleep (REM), participants maintained control over a virtual cybertruck, using muscle contractions in their limbs to intentionally avoid obstacles represented by bright flashes of light. Though the participants didn’t actually dream they were driving, the basic concept of responding to cues while otherwise asleep could lead to new ways of bridging the space between dream-states and the waking world. In REM sleep, most muscles are largely paralyzed, but during lucid dreams, micro-contractions can still be made. REMspace developed special equipment that can detect tiny twitches of leg and arm muscles during sleep.”

> https://www.sciencealert.com/lucid-dreamers-drove-virtual-cars-while-asleep-in-incredible-experiment

“Participants spent one to four nights in the laboratory. First, before falling asleep, they were trained to control a virtual car with EMG sensors by tensing their muscles: they tensed their biceps or forearm muscles to make turns and tensed their quadriceps to drive. If an obstacle appeared in front of the avatar of the car, two diodes indicated the need to turn through the participant’s closed eyes (the brightness was tuned for each participant individually). Once a turn was made, the diodes were switched off automatically. Tensing the right arm made the avatar turn right (45°), and tensing the left arm made the avatar turn left (45°). Tensing both legs moved the avatar. The duration for which the muscles were tensed affected the distance of the forward movement and the degrees of a turn.”

> Raduga, M., & Shashkov, A. (2024, March 25). A way to operate a smart home from lucid dreams. https://doi.org/10.11588/ijodr.2024.1.100322

[2] Fatuzzo et al 2023, Salameh et al 2024

Leave a comment