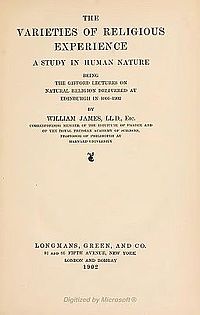

An excerpt from The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature (1902), chapter Conversion (p176):

“When I say ‘Soul,’ you need not take me in the ontological sense unless you prefer to; for although ontological language is instinctive in such matters, yet Buddhists or Humians can perfectly well describe the facts in the phenomenal terms which are their favourites. For them the soul is only a succession of fields of consciousness: yet there is found in each field a part, or sub-field, which figures as focal and contains the excitement, and from which, as from a centre, the aim seems to be taken. Talking of this part, we involuntarily apply words of perspective to distinguish it from the rest, words like ‘here,’ ‘this,’ ‘now,’ ‘mine,’ or ‘me’; and we ascribe to the other parts the position ‘there,’ ‘then,’ ‘that,’ ‘his’ or ‘thine,’ ‘it,’ ‘not me.’ But a ‘here’ can change to a ‘there,’ and a ‘there’ become a ‘here,’ and what was ‘mine’ and what was ‘not mine’ change their places.

What brings such changes about is the way in which emotional excitement alters. Things hot and vital to us to-day are cold tomorrow. It is as if seen from the hot parts of the field that the other parts appear to us, and from these hot parts personal desire and volition make their sallies. They are in short the centres of our dynamic energy, whereas the cold parts leave us indifferent and passive in proportion to their coldness.

Whether such language be rigorously exact is for the present of no importance. It is exact enough, if you recognise from your experience the facts which I seek to designate by it.

Now there may be great oscillation in the emotional interest, and the hot places may shift before one almost as rapidly as the sparks that run through burnt-up paper. Then we have the wavering and divided self we heard so much of in the previous lecture. Or the focus of excitement and heat, the point of view from which the aim is taken, may come to lie permanently within a certain system; and then, if the change be a religious one, we call it a conversion, especially if be by crisis, or sudden.

Let us hereafter, in speaking of the hot place in a man’s consciousness, the group of ideas to which he devotes himself, and from which he works, call it the habitual centre of his personal energy. It makes a great difference, as regards any set of ideas which he may possess, whether they become central or remain peripheral in him. To say that a man is ‘converted’ means, in these terms, that religious ideas, previously peripheral in his consciousness, now take a central place, and that religious aims form the habitual centre of his energy.

Now if you ask of psychology just how the excitement shifts in a man’s mental system, and why aims that were peripheral become at a certain moment central, psychology has to reply that although she can give a general description of what happens, she is unable in a given case to account accurately for all the single forces at work. Neither an outside observer nor the Subject who undergoes the process can fully explain how particular experiences are able to change one’s centre of energy so decisively, or why they so often have to bide their hour to do so. We have a thought, or we perform an act, repeatedly, but on a certain day the real meaning of the thought peals through us for the first time, or the act has suddenly turned into a moral impossibility. All we know is that there are dead feelings, dead ideas, and cold beliefs, and there are hot and live ones; and when one grows hot and alive within us, everything has to re-crystallize about it. We may say that the heat and liveliness mean only the ‘motor efficacy,’ long deferred but now operative, of the idea; but such talk itself is only a circumlocution, for whence the sudden motor efficacy? And our explanations then get so vague and general that one realizes all the more the intense individuality of the whole phenomenon.

In the end we fall back on the hackneyed symbolism of mechanical equilibrium. A mind is a system of ideas, each with the excitement it arouses, and with tendencies impulsive and inhibitive, which mutually check or reinforce one another. The collection of ideas alters by subtraction or by addition in the course of experience, and the tendencies alter as the organism gets more aged. A mental system may be undermined or weakened by this interstitial alteration just as a building is, and yet for at time keep upright by a dead habit. But a new perception, a sudden emotional shock, or an occasion which lays bare the organic alteration, will make the whole fabric fall together, and then the centre of gravity sinks into attitude more stable, for the new ideas that reach the centre in the rearrangement seem now to be locked there, and the new structure remains permanent.

Formed associations of ideas and habits are usually factors of retardation in such changes of equilibrium. New information, however acquired, play an accelerating part in the changes; and the slow mutation of our instincts and propensities, under the ‘unimaginable touch of time’ has an enormous influence. Moreover, all these influences may work subconsciously or half unconsciously. And when you get a Subject in whom the subconscious life is largely developed, and in whom motives habitually ripen in silence, you get a case of which you can never get a full account, and in which, both to the Subject and the onlookers, there may appear an element of marvel. Emotional occasions, especially violent ones, are extremely potent in precipitating mental rearrangements. The sudden and explosive ways in which love, jealousy, guilt, fear, remorse, or anger can seize upon one are known to everybody. Hope, happiness, security, resolve, emotions characteristic of conversion, can be equally explosive. And emotions that come in this explosive way seldom leave things as they found them.”

Leave a comment